According to the Census Bureau, in 1890, 104,805 physicians practiced medicine in the United States, including 115 Black women and 909 Black men. By 1920, the number of physicians nationwide had grown to 144,977, and the number of Black male physicians had increased to 3,495, but the number of Black females had declined to 65. The decline was due in large part to a growing resistance to women practicing medicine (the number of white female physicians had also declined).1

Women faced what seemed like insurmountable obstacles when trying to gain admission to medical school. Aside from the sexism displayed by males of both races, African American women endured racism from their white counterparts. While some white women may have been accepted in all white schools, Black women often went to medical schools established for women. These schools were highly regarded in the profession but the number of schools were limited and the number of African Americans accepted was not numerous although each class generally enrolled 2-3 Black women.

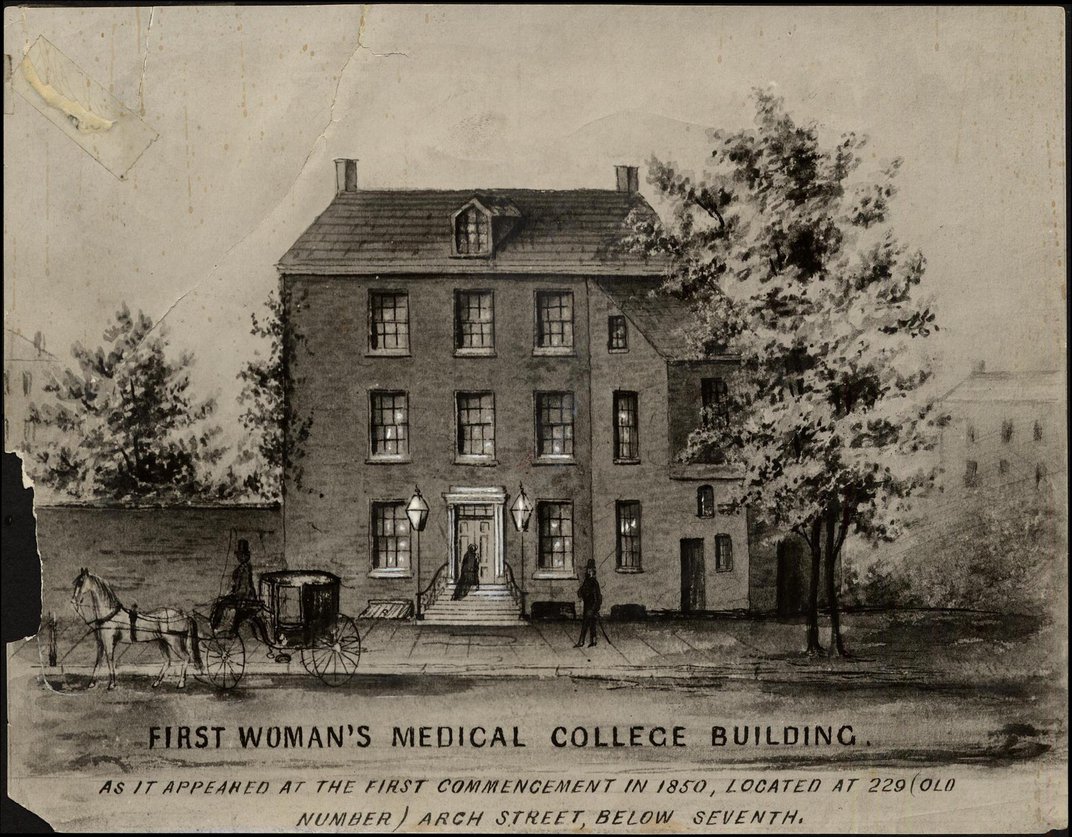

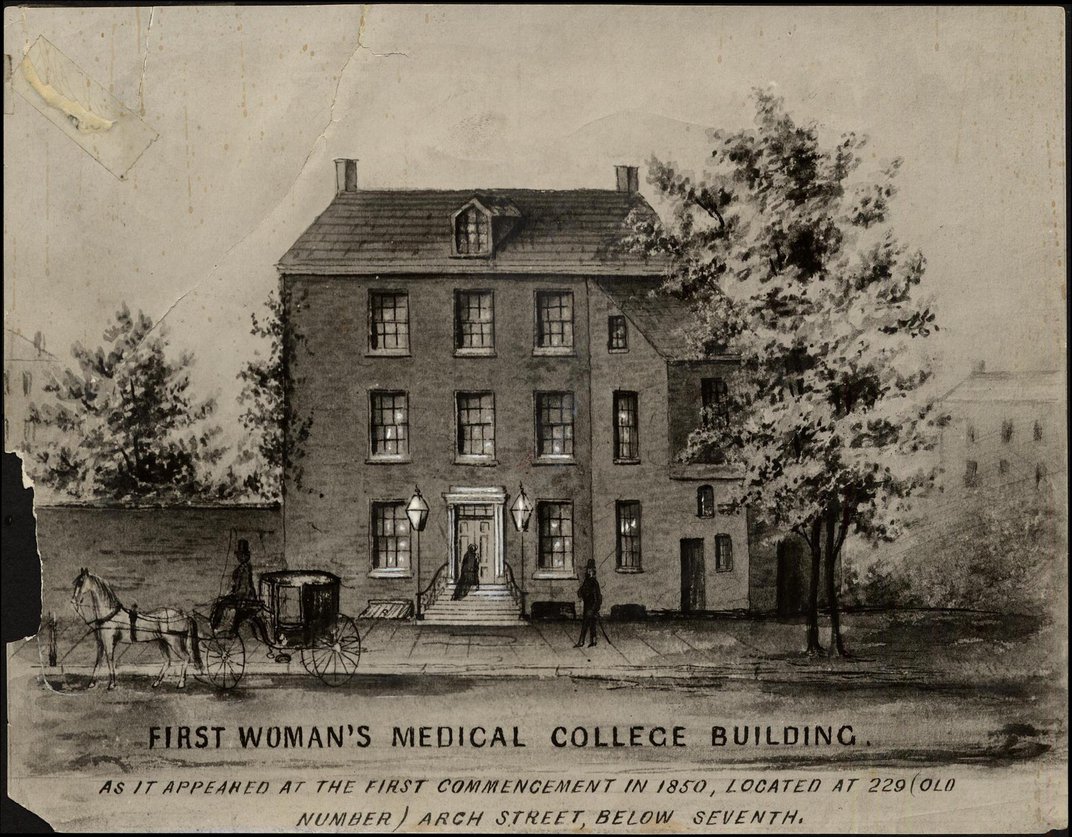

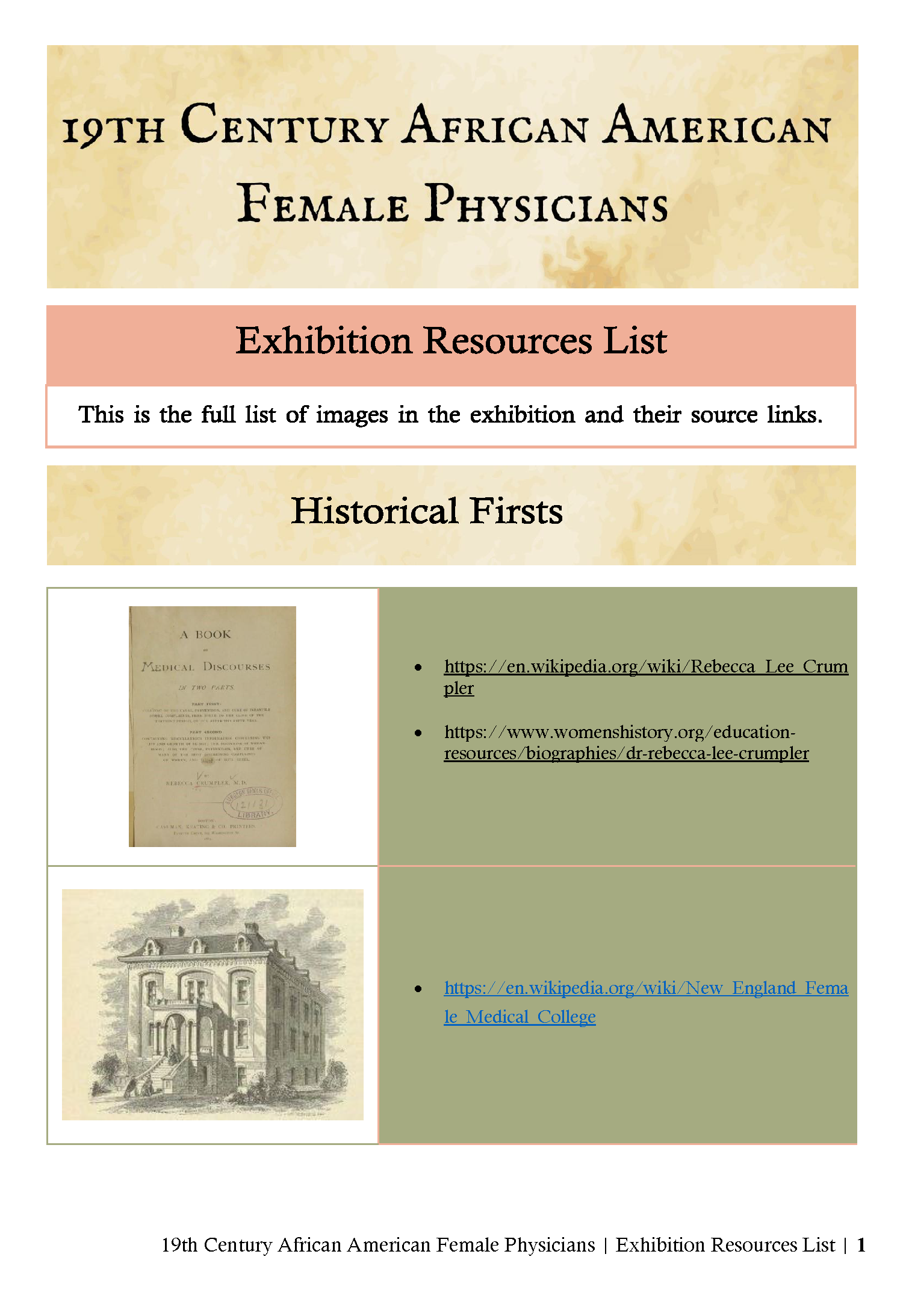

Schools such as the Female Medical College of Pennsylvania, the New England Female Medical College, and Philadelphia's Women's Medical College of Pennsylvania had been established for women so that they like their male counterparts could learn without the prejudice of fellow students and professors. To that end in the nineteenth century, the Women's Medical College of Pennsylvania graduated more Black and Native American female doctors than other medical institutions.

Schools such as the Female Medical College of Pennsylvania, the New England Female Medical College, and Philadelphia's Women's Medical College of Pennsylvania had been established for women so that they like their male counterparts could learn without the prejudice of fellow students and professors. To that end in the nineteenth century, the Women's Medical College of Pennsylvania graduated more Black and Native American female doctors than other medical institutions.

Upon graduation, several physicians sought medical licenses in mostly southern states. They fought some of the same battles to become licensed as they had fought to enroll medical school. Dr. Lucy Manetta Hughes Brown, became the first Black female physician in North Carolina and also the editor of the first black medical journal the Hospital Herald.3 Dr. Artishia Garcia Gilbert was the first African American to pass the medical boards in Kentucky.4 Dr. Matilda Arabella Evans was the first African American woman to obtain a license in South Carolina.5 Dr. Rebecca J. Cole was the co-founder of the Women’s Directory Center (1873), which provided free medical and legal services for poor women.6 Dr. Halle Tanner Dillon Johnson established a nurses’ training school in Tuskegee and the Lafayette Dispensary, where she compounded her own medicines.

These are just five of the pioneering African American women, who struggled against the attitude towards women and the attitude towards African Americans, to overcome prejudices and leave a lasting legacy of service. These women and others had observed the lack of medical care given not only to former slaves but to Black people and poor people in general. The plight of people prompted many to become active in education, social work, suffrage, public health, missionary work and other civic endeavors.

This guide aims to showcase 27 19th Century African American female physicians, detailing information on their lives and contributions to the medical profession.

1 Physicians by Vanessa Northington Gamble Source: Black Women in America, Second Edition

2 Anderson, Caroline Virginia Still Wiley by Geraldine Rhoades Source: African American National Biography

3 Brown, Lucy Manetta Hughes by Geraldine Rhoades Beckford Source: African American National Biography

4 Notable Kentucky African Americans Database

5 Changing the Race of Medicine. Celebrating America’s Women Physician. U.S. National Library of Medicine Office of Research on Women’s Health

6 Contemporary Black Biography Gale Detroit MI 2003.

Women faced what seemed like insurmountable obstacles when trying to gain admission to medical school. Aside from the sexism displayed by males of both races, African American women endured racism from their white counterparts. While some white women may have been accepted in all white schools, Black women often went to medical schools established for women. These schools were highly regarded in the profession but the number of schools were limited and the number of African Americans accepted was not numerous although each class generally enrolled 2-3 Black women.

Schools such as the Female Medical College of Pennsylvania, the New England Female Medical College, and Philadelphia's Women's Medical College of Pennsylvania had been established for women so that they like their male counterparts could learn without the prejudice of fellow students and professors. To that end in the nineteenth century, the Women's Medical College of Pennsylvania graduated more Black and Native American female doctors than other medical institutions.

Schools such as the Female Medical College of Pennsylvania, the New England Female Medical College, and Philadelphia's Women's Medical College of Pennsylvania had been established for women so that they like their male counterparts could learn without the prejudice of fellow students and professors. To that end in the nineteenth century, the Women's Medical College of Pennsylvania graduated more Black and Native American female doctors than other medical institutions.

Upon graduation, several physicians sought medical licenses in mostly southern states. They fought some of the same battles to become licensed as they had fought to enroll medical school. Dr. Lucy Manetta Hughes Brown, became the first Black female physician in North Carolina and also the editor of the first black medical journal the Hospital Herald.3 Dr. Artishia Garcia Gilbert was the first African American to pass the medical boards in Kentucky.4 Dr. Matilda Arabella Evans was the first African American woman to obtain a license in South Carolina.5 Dr. Rebecca J. Cole was the co-founder of the Women’s Directory Center (1873), which provided free medical and legal services for poor women.6 Dr. Halle Tanner Dillon Johnson established a nurses’ training school in Tuskegee and the Lafayette Dispensary, where she compounded her own medicines.

These are just five of the pioneering African American women, who struggled against the attitude towards women and the attitude towards African Americans, to overcome prejudices and leave a lasting legacy of service. These women and others had observed the lack of medical care given not only to former slaves but to Black people and poor people in general. The plight of people prompted many to become active in education, social work, suffrage, public health, missionary work and other civic endeavors.

This guide aims to showcase 27 19th Century African American female physicians, detailing information on their lives and contributions to the medical profession.

1 Physicians by Vanessa Northington Gamble Source: Black Women in America, Second Edition

2 Anderson, Caroline Virginia Still Wiley by Geraldine Rhoades Source: African American National Biography

3 Brown, Lucy Manetta Hughes by Geraldine Rhoades Beckford Source: African American National Biography

4 Notable Kentucky African Americans Database

5 Changing the Race of Medicine. Celebrating America’s Women Physician. U.S. National Library of Medicine Office of Research on Women’s Health

6 Contemporary Black Biography Gale Detroit MI 2003.

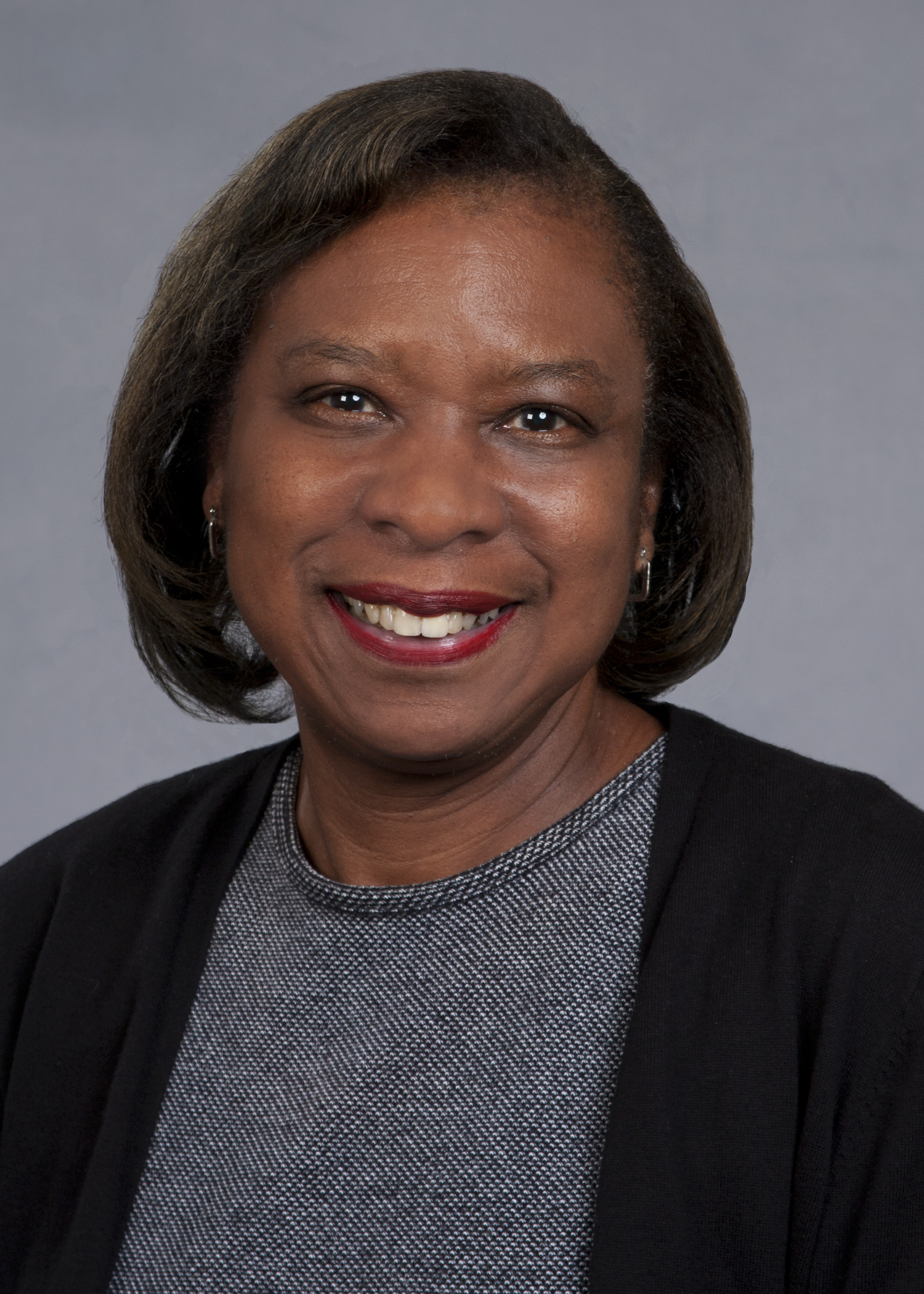

Thank you for visiting the 19th Century African American Female Physicians Traveling Exhibition.

Your feedback is important to us. Share your thoughts about the Exhibit and Resource guide. Please fill out the feedback form using this link, or use the QR Code below.

You can also share your comments via email.

Your feedback is important to us. Share your thoughts about the Exhibit and Resource guide. Please fill out the feedback form using this link, or use the QR Code below.

You can also share your comments via email.

Mary Elizabeth Britton (1858-1925)

Physician, Educator, Journalist, Social Activist, Church Worker

Mary, one of seven born free in Lexington, Kentucky, would become an African American physician, educator, suffragist, journalist, and civil rights activist and received a classical education. Her father, Henry, free born of Spanish/Indian heritage, was a carpenter and later a barber and her mother, Laura, an enslaved mistress to Kentucky statesman Thomas Francis Marshall, nephew of John Marshall, was emancipated at age 16.1

From 1871 to 1874, Mary attended Berea College, the first institution of higher learning to admit blacks in the state of Kentucky.2 Mary lost her father before her graduation in March 1874 and her mother in July 1874.3

Mary Britton taught school to support herself but it was as a journalist where she was recognized as one the leading female writer. She wrote for numerous papers including the Courant, the Cleveland Gazette, the Lexington Herald, the Indianapolis World, the Cincinnati Commercial, and the Ivy. She used the pen name “Meb” or “Aunt Peggy” when writing on matters of interest to children and young adults.4

As part of her activism, Mary spoke on several occasions about women and racism. During a speech to the Joint Railroad, she questioned the white supremacists' assumptions about their monopoly on virtue, intelligence and aestheticism - reminding the legislators of the horrors of slavery and atrocities by whites that were allowed.5 Aside from civil rights, she was active in suffrage.. In a speech given at the Ninth Annual Convention of the Kentucky Negro Education Association, 1897, her second speech which was published as “Woman's Suffrage: A Potent Agency in Public Reform"6, she stated, "If woman is the same as man then she has the same rights, if she is distinct from man then she has a right to the ballot to help make laws for her government." 7

In 1897, she resigned from teaching, to begin working in the Battle Creek Sanitarium, where she learned hydrotherapy, phototherapy, electrotherapy and mechanotherapy, and began studying medicine at the American Missionary College of Medicine in Chicago. After medical school she returned to Lexington, applied for a license to practice medicine in Fayette County8 and became the first African American woman licensed to practice medicine in Lexington, Kentucky.

As a member of the Seventh Day Adventist Church, her specialties were hydrotherapy, electrotherapy, and massage.9

Dr. Britton retired from her practice in 1923 at 68 and died in 1925. Her library was given to the Seventh-Day Adventist Church and her estate to her sister Julia Britton Hooks, mother of Benjamin Hooks, former Executive Director of NAACP.

Picture Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mary_E._Britton

1 Byars, Lauretta Flynn (1996). "Mary Elizabeth Britton (1858 - 1925)". In Smith, Jessie Carney (ed.). Notable Black American Women, Book II. Detroit, MI: Gale Research Inc. pp. 55–56.

2 Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mary_E._Britton (Accessed November 11, 2019)

3Black Women in America: An Historical Encyclopedia. Editors: Darlene Clark Hines, Elsa Barkley, Rosalyn Terborg-Penn, Indiana University Press, 1993, p. 167

4 Ibid

5 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mary_E._Britton (Accessed November 11, 2019)

6,7,8 McDaniel, Karen Cotton (Spring 2013). "Mary Ellen Britton: A Potent Agent for Public Reform". The Griot: the Journal of African American Studies. 32 (1): 52–61.9

9Notable

Lucy Manetta Hughes Brown (1863-1911)

Physician, Educator, Institutional Founder/Benefactor

Lucy was born in Mebane, North Carolina in April 1863. She attended Scotia Seminary and graduated in 1885 after which in 1890, she matriculated at the Women’s Medical College of Philadelphia graduating in 1894. Upon graduation, Dr. Brown returned to North Carolina and became the first African American woman to receive a professional license from the North Carolina Medical Board.1 She practiced medicine in her home state for two years before going to Charleston, South Carolina, where she became the first female African-American physician Charleston.2

With the help of several African Americans, she helped to establish the Cannon Hospital and Training School. Dr. Brown also helped to edit the state's first black medical periodical, the Hospital Herald, which was founded in 1898. In 1902, the British Journal of Nursing recognized her as a leader in her profession in South Carolina.3

Because of rapidly deteriotating health, she retired from her practice in 1904 and died on June 26, 1911.4

Picture Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lucy_Hughes_Brown

1South Carolina Encyclopedia, http://www.scencyclopedia.org/sce/entries/brown-lucy-hughes/ Written by Elizabeth D. Schafer (Accessed November 11, 2019)

2 Ibid

3Wikipedia Lucy Huges Brown https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lucy_Hughes_Brown

4Black Women in America: An Historical Encyclopedia. Editors: Darlene Clark Hine, Elsa Barkley Brown, Rosalyn Terborg-Penn. Indiana University Press, 1993, page 182

Mary Louise Brown (1868-1927)

Physician, Teacher

Mary Louise was born in 1868 in Baltimore, Maryland to John Mifflin Brown and Mary L. Lewis Brown. Her father was a bishop in the African Methodist Episcopal Church and the family frequently moved. Since this was during the time of Reconstruction, she and her eight siblings took advantage of the opportunities being afforded.1

She attended the Normal School for Colored Girls in Washington, D.C. and upon graduation began her teaching career, teaching English. Mary Louise attended Howard University Medical school at night graduating in 1898. In 1899 and 1900, she attended post graduate education at the University of Edinburgh. When she returned to the United States, she opened her practice at 1813 Vermont Avenue in the District of Columbia. Dr. Brown continued teaching and because of her advanced degree, she taught science, which raised her significantly. While teaching she often treated her students for free.

With the outbreak of World War I, Dr. Brown received a commission from the American Red Cross and left for France in 1918 to care for wounded soldiers. Women’s organizations such as the American Medical Women’s Association and National American Woman Suffrage Association lobbied for the commission and military service records. Women received the commission but not the military service records that had been accorded to men. At the time that she received the commission she was one of two Black women to do so, the other was Dr. Harriet Rice (1866-1958).2 While in France, she suffered both racism and the sexism. The sexism from the military and the racism from what the United States government told the French about black people until the French authorities retrieved the information published by the United States.2

Upon her return to the United States, she contued her teaching and medical practice until her sudden death on March 9, 1927.

1 Mary Louise Brown https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mary_Louise_Brown#CITEREFJensen2008 (Accessed July 13, 2021)

2 The untold story of women who risked their lives to do good – and get their rights. Opinion by Kate Clarke Lemay (Access July 13, 2021)

Rebecca J. Cole (1846-1922)

Physician, Advocate

Rebecca Cole was born free on March 16, 1846 in Philadelphia. She attended the Institute for Colored Youth (ICY), later known as Cheyney University during this time, Rebecca was recognized for her talent in classics and mathematics.

Dr. Cole graduated from the Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania in 1867, under the supervision of Ann Preston, the first woman dean of the school. Her graduate thesis was "The Eye and it Appendages."2 After graduation, she went to New York and worked at Elizabeth Blackwell's New York Infirmary for Women and Children to gain clinical experience and was assigned the post of sanitary visitor.1 The Infirmary was run and entirely owned by women.

Later, Dr. Cole moved to South Carolina, where she practiced for a few years but returned to Philadelphia, where she often made house calls to some of the worse neighborhoods stressing hygienic practices to women, for them and the family, especially babies. In 1873, in Philadelphia with fellow physician Charlotte Abbey, she open the Woman’s Directory Center providing medical and legal services to women and children.3 The Directory provided these services to destitute women, particularly new and expecting mothers, and worked with local authorities to help prevent and fairly prosecute child abandonment.4 In 1876, she served as a representative for the Ladies’ Centennial Committee of Philadelphia after winning the argument that there should not be a separate auxiliary for colored ladies.

In 1901, after 25 years of her work in the slums, Dr. Cole was involved in a well-publicized dispute with W.E.B. DuBois as to the reason that blacks were dying of consumption. Her response to DuBois, appearing in the periodical The Women’s Era was “[H]osts of the poor are attended by young, inexperienced white physicians. They inherited the traditions of their elders, and let a black patient cough, they immediately have visions of tubercles... he writes ‘tubercolosis’ [sic] and heaves a great sigh of relief that one more source of contagion is removed.”5

Understanding the connection between racial inequality and health disparities, she advocated for open air spaces condemning landlords that crowded people together like cattle to make a profit and fair treatment of patients regardless of race.

After practicing medicine for 50 years Dr. Cole retired and died in 1922.

To pay tribute to her pioneering work, Dr. Cole, was honored in the 2015 Innovators Walk of Fame at University of Pennsylvania.6

Picture Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rebecca_Cole

1 Changing the Face of Medicine https://cfmedicine.nlm.nih.gov/physicians/biography_66.html (Accessed November 11, 2019)

2 A Movable Archives https://amovablearchives.blogspot.com/2009/02/from-collections-dr-rebecca-cole.html (Accessed November 11, 2019)

3 Black Women in America: An Historical Encyclopedia. Editors: Darlene Clark Hine, Elsa Barkley Brown, Rosalyn Terborg-Penn, Indian University Press, 1993, p. 262.

4 The Woman Who Challenged the Idea that Black Communities Were Destined for Disease https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/woman-challenged-idea-black-communities-destined-disease-180969218/ (Accessed November 20, 2019)

5 Ibid.

6 University of Pennsylvania Almanac Science Center: Celebrating Women Innovators in 2015 Class of the Innovators Walk of Fame, October 27, 2015, Volume 62, No. 11

Rebecca Davis Lee Crumpler (1831-1895)

Physician

Rebecca Davis, was born free in 1831 in Christiana, Delaware but was raised by an aunt in Philadelphia who provided nursing care to people of the neighborhood. By 1852, Rebecca living in Charlestown, Massachusetts, worked as a nurse for eight years when she was admitted to the New England Female Medical College. Graduating in 1864, receiving her Doctress of Medicine, she became the first African-American woman to receive a medical degree and the school’s only black alumna.

Dr. Crumpler's first practice was in Boston but during Reconstruction she moved to Richmond to work with the Freedman’s Bureau and because she felt that it was “a proper field for real missionary work, and one that would present ample opportunities to become acquainted with the diseases of women and children. During my stay there nearly every hour was improved in that sphere of labor. The last quarter of the year 1866, I was enabled… to have access each day to a very large number of the indigent, and others of different classes, in a population of over 30,000 colored.”1 After marrying, Arthur Crumpler, she had actively stopped practicing medicine. Not totally detached from the field, in 1883, she published “A Book of Medical Discourses’ in which she discussed her desire to become a physician was to relieve the suffering of others.

Dr. Crumpler died on March 9, 1895 in Fairview, Massachusetts.

In honor of her work in 1989, the first medical society for Black women was founded named the Rebecca Lee Society.

1 Kentake Page http://kentakepage.com/rebecca-davis-lee-crumpler-first-black-woman-awarded-a-medical-degree-in-the-united-states/ (Accessed November 20, 2019)

Matilda Arabella Evans (1872-1935)

Physician, Surgeon, Educator, Journalist, Community Activist

Matilda was born in Aiken, South Carolina, the eldest of three children to Anderson and Harriet Evans. Her early life was spent working a farm alongside her family. With the help of Martha Schofield, a Quaker, she obtained the funds and applied to Oberlin College in Ohio.1 After graduation she attended the Women’s Medical College of Philadelphia graduating in 1897 with specialties in obstetrics, gynecology, and surgery.2 Upon graduation, Dr. Evans returned to South Carolina, becoming the first African American female physician to practice in South Carolina3, and the first African American woman surgeon4 . In Columbia, South Carolina, as the only female physician,5 she opened her practice first in her home and then founded the Taylor Lane Hospital in 1901 as the first black owned hospital in Columbia. Here, Dr. Evans practiced obstetrics, gynecology, hygienics and pediatrics and provided care to a mixed clientele, rich and poor, Black and white. With money received from wealthy white patients, she provided free or subsidized care to black patients, especially women and children. Dr. Evans believed that health care was a citizenship right and a governmental responsibility and she therefore, petitioned the Board of Health of South Carolina to provide her with free vaccines for the children, while encouraging the Colombia Black community to demand those citizenship rights. Her main concern was the health of the children, to that end she obtained permission to examine the children in public schools and convinced the school system to implement a permanent program to provide students with regular examinations.6

After Taylor Lane Hospital burned, Dr. Evans opened St. Luke’s Hospital and Training School for Nurses, the fourth hospital in the country to operate a school for nurses. It is the country’s oldest hospital-based diploma school in continuous operation.7 In 1916, she created the Negro Health Association of South Carolina and volunteered in the Medical Service Corps of the United States Army during World War I.8 The purpose of the Association was to teach South Carolinians proper health care procedures. Matilda also served as vice president of the National Medical Association.

Dr. Evans acquired 20 acres of land and resumed farming for the community and established a community health organization, community center and boy’s pool. In 1922, she became the president of the South Carolina’s Palmetto Medical Association, making her the first black female to serve in that capacity and she established the Negro Health Journal of South Carolina, as a resource for people to become involved in their own healthcare.9

Although she never married, she was able to adopt and raise seven children in addition to fostering several more.

Dr. Evans died in Columbia, South Carolina on November 17, 1935.

Picture Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Matilda_Evans

1 Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Matilda_Evans (Accessed November 15, 2019)

2 Columbia City of Women https://www.columbiacityofwomen.com/honorees/matilda-arabella-evans-md (Accessed November 15, 2019)

3 Changing the Face of Medicine https://cfmedicine.nlm.nih.gov/physicians/biography_107.html (Accessed November 15, 2019)

4 Annals of Surgery Pories, Susan E. et al. 269(2);199-205 (Accessed November 15, 2019)

5 https://www.columbiacityofwomen.com/honorees/matilda-arabella-evans-md (Accessed November 15, 2019)

6 UP/Closed https://upclosed.com/people/matilda-evans-1/ (Accessed November 15, 2019)

7 Kentake & Love Affair with Black History http://kentakepage.com/matilda-evans-medical-pioneer-of-south-carolina/ (Accessed November 15, 2019)

8 BlackPast https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/evans-matilda-1872-1935/ (Accessed November 15, 2019)

9 Ibid

10 https://www.columbiacityofwomen.com/honorees/matilda-arabella-evans-md (Accessed November 15, 2019)

11 http://kentakepage.com/matilda-evans-medical-pioneer-of-south-carolina/ (Accessed November 15, 2019)

Sarah Helen McCurdy Fitzbutler (1847-1923)

Physician

Sarah Helen McCurdy was free born in Pennsylvania on October 13, 1847. Her father, a prosperous cattle and horse rancher moved the family to southern Ontario. In 1866, she married Henry Fitzbutler. Her husband went on to be the first African American to earn a degree from the University of Michigan.

With her children grown, Sarah entered the Louisville National Medical College and upon graduation became the first African American woman licensed in Kentucky. After Henry’s death in 1901, she continued her medical practice in obstetrics and gynecology. Dr. Fitzbutler became superintendent of the College’s auxiliary hospital on Madison Street, and also supervised the nursing program at the College. In Abraham Flexner’s 1909 inspection tour of medical schools and their facilities, he found her Hospital to be one of the cleanest and best run in the country.1

Towards the end of her life, she moved to Chicago, where some of her children were pursuing their own careers, and died on January 13, 1923.2

Image UofL School of Medicine https://louisville.edu/medicine/studentaffairs/student-involvement/advisory-colleges-1/fitzbutler-college

1 UofL School of Medicine Fitzbutler College http://louisville.edu/medicine/studentaffairs/student-involvement/advisory-colleges-1/fitzbutler-college (Accessed November 11, 2019)

2 The Kentucky African American Encyclopedia edited by Gerald L. Smith, Karen Cotton McDaniel, John A. Hardin University Press of Kentucky, c2015 page 182

Louise Celia "Lulu" Fleming (1862-1899)

Physician, Missionary

Louise Fleming was born into slavery on the Col. Lewis Michael Fleming Hibernia Plantation in Hibernia, Clay County, Florida. In 1885 she graduated from Shaw University in North Carolina, as class valedictorian.1 She would become the first African-American woman commissioned by the Women's American Baptist Foreign Missionary Society to work in Africa, traveling from the United States to what is present-day Zaire for five years.2 Lulu became ill and returned to the United States to recover. While she was recuperating she enrolled in Shaw University’s Leonard Medical School in 1891 but transferred to the Women’s Medical College of Philadelphia, graduating in 1895.

Upon graduation, Dr. Fleming was stationed at Irebu in the Upper Congo and to the Bolengi station thus making her the first African American woman to be sent on missionary work in Africa.3 Lulu trained several Congolese men and women in basic health principles. During this time, she contracted African sleeping sickness and returned to the United States in 1898.

She passed away one year later on June 20, 1899.4

Image Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Louise_Celia_Fleming

1 This day in Black History: Jan. 28, 1862 https://www.bet.com/news/national/2013/01/28/this-day-in-black-history-jan-28-1862.html (Accessed November 5, 2019)

2 Ibid

3 BCNN1 Remembering Louise Celia Fleming, the First Black American Female Missionary to Serve in Africa https://blackchristiannews.com/2019/01/remembering-louise-celia-fleming-the-first-black-american-female-missionary-to-serve-in-africa/ (Accessed November 5, 2019)

4 This day in Black History: Jan. 28, 1862 https://www.bet.com/news/national/2013/01/28/this-day-in-black-history-jan-28-1862.html (Accessed November 5, 2019)

Justina Warren Ford (1871-1952)

Physician

Justina Warren was born in Knoxville, Illinois on January 22, 1871. Growing up Justina often accompanied her mother, a nurse, on calls thus sparking her interest in medicine. In 1899, she graduated from Hering Medical College and headed south to Alabama. The reason is unknown but the presence of Booker T. Washington may have played a part. However, instead of going to Tuskegee, she settled in Normal, Alabama becoming resident physician at what is now Alabama A&M University.

In 1902, Dr. Ford tired of the Jim Crow South, decided to move to Denver, Colorado hoping for better opportunities. When she applied for her license to practice medicine, she was told by the clerk, "I feel dishonest taking a fee from you. You've got two strikes against you to begin with. First of all, you're a lady, and second, you're colored."1 Dr. Ford received her license becoming the first African American woman licensed in Colorado and proceeded to set up her practice specializing in obstetrics, gynecology, and pediatrics2 After setting up her practice, Justina learned that the Denver General Hospital accepted neither black patients nor physicians.3 She was also denied entrance to the Denver and Colorado Medical Societies. These denials only made her more determined and her practice served not only poor Blacks, but poor Whites, Indians, Japanese, and other non-English speaking immigrants. Dr. Ford made house calls first by having her husband drive her, then taking a cab or riding a horse so that she could serve her patients especially when providing obstetrical care. She believed a home birth was always better. Her dedication to her patients was demonstrated by not only providing medical care but sometimes groceries and coal and becoming conversant in seven languages including native American languages, Spanish, Italian and Japanese. Payments were not always in cash but in goods and services.

Dr. Justina Ford’s practice lasted 50 years and she became known as The Lady Doctor having delivered nearly 7,000 babies.4 In 1950, she gained admission to the Denver and Colorado medical societies5 and was allowed to practice at the Denver General Hospital.6 At that time she was still the only African American and female doctor in Colorado.7

Four months before her death, she is quoted as saying, "...When all the fears, hate, and even some death is over, we will really be brothers as God intended us to be in this land. This I believe. For this I have worked all my life."6

In 1988, Ford's home in Five Points, Denver, was converted into the Black American West Museum and Heritage Center. One room is devoted to an exhibition of her life and work.8

Dr. Ford was admitted to the Colorado Women's Hall of Fame in 1985 and was named a "Medical Pioneer of Colorado" by the Colorado Medical Society in 1989. In 1998, a sculpture of Dr. Ford holding a baby, made by Jess E. DuBois, was erected outside her house.8

Goodwill of Colorado https://cfmedicine.https://goodwillcolorado.org/2022/02/18/black-history-month-dr-justina-ford-colorados-first-black-female-physician/

1 https://cfmedicine.nlm.nih.gov/physicians/biography_118.html (Accessed November 5, 2019)

2 https://ourcommunitynow.com/local-culture/our-coloradans-then-justina-ford-breaking-barriers-in-colorado-medicine (Accessed November 5, 2019)

3 https://www.cogreatwomen.org/project/justina-ford-md/ (Accessed November 5, 2019)

4 Alchetron https://alchetron.com/Justina-Ford (Accessed November 5, 2019)

5 AlabamaYesterdays https://alabamayesterdays.blogspot.com/2016/08/dr-justina-ford-at-alabama-and-beyond.html (Accessed November 5, 2019)

6 Changing the Face of Medicine 2003 https://cfmedicine.nlm.nih.gov/physicians/biography_118.html (Accessed November 5, 2019)

7 Alchetron https://alchetron.com/Justina-Ford (Accessed November 5, 2019)

8 Ibid

Sarah Marinda Loguen Fraser (1850-1933)

Physician, Pharmacist/Druggist

Sarah was born in Syracuse, New York to Caroline Storum and Reverend Jermain Wesley Loguen, livelong abolitionists. Her home was a stop on the Underground Railroad where her family provided food, shelter and basic medical care to over 1500 escaped slaves en route to Canada.1 Being denied medical access to medical institutions, the Loguens employed traditional Iroquois healing techniques.2

In 1873, in Washington, DC, Sarah witnessed indifference when a boy was struck by a cart and people were reluctant to help. On her way back to Syracuse, she vowed to herself to become a doctor. After studying under Dr. Michael Benedict, she was admitted to the Syracuse University School of Medicine, one of the first institutions of higher learning to admit men and women of all races as students. 3 Graduating in 1873, Dr. Fraser became the first woman to receive a medical degree from that school. Shortly after her graduation, one of her classmates proposed marriage to her. He confessed that he had loved her from the start, asserted that his whiteness and her blackness did not matter, and even suggested that a black female physician was a social freak who needed a white male physician alongside her to ensure her professional survival. She declined his proposal, which she in no way expected, and told him that she had already seen so much suffering among her own people that she could not abandon them by marrying a white man. She also told him that her missions was to build strong and healthy black bodies, and so continue her father’s work to improve the lives of Afican-Americans.4

Dr. Fraser began her internship in 1876 at the Women’s Hospital in Philadelphia and there she met a white women from Nashville, Tennessee just 16 miles from Rev. Loguen’s birthplace. Everyone said they looked like twin sisters. They were both soon astonished to discover that they were in fact cousins. The white woman was so flustered and embarrassed by this revelation that she resigned.5 While at the Women’s Hospital, Dr. Fraser conducted an experiment by giving agitated patients some pastel colored yarn to knit with. She did this because she remembered how the colors calmed her. These trials had a remarkable calming effect on the patients, and are thought to be a very early example of usage of the psychology of color in a hospital setting.6 In 1878, Dr. Loguen accepted a six month appointment at New England Hospital for Women and Children. She then moved to Washington, DC, and established her own medical practice.

In 1882, she married Dr. Charles Fraser, pharmacist and plantation owner in Puerto Plata, Dominican Republic. With no previous knowledge of Spanish, she passed the certification in 1884 at the University of Santo Domingo and became first woman doctor and first pediatric specialist in the Dominican Republic and was given the title of Miss Doc by the people. By law, she could only treat women and children and her husband had to give permission.7

After the death of her husband in 1894, Sarah tried to run his various businesses including the pharmacy and maintain her practice but returned to Washington, DC in the fall 1896. She was not ready for post reconstruction America and Jim Crow. In an effort to educate her daughter, she moved to France enrolling her daughter Georgoria in a boarding school outside of Paris. In 1901, She moved back to Syracuse since her daughter was attending Syracuse University and resumed her pediatric practice and became a mentor to the midwives in the area.6 In 1907, Sarah moved in with her widowed sister Amelia in Washington, DC and accepted the position of resident physician at the Blue Plains Industrial School for Colored Boys, The job was a disaster, Dr. Fraser was expected to care for 14 boys, some with behavioral problems, do all the cooking, cleaning and any work deemed necessary by the superintendent. On a visit her daughter packed up her belongings and despite the threats of lawsuits removed her mother. The school never did file suit.

In 1917, she moved in with her daughter and her husband until her death in 1933, from kidney disease and Alzheimer’s disease. In the 1920, US Census, Dr. Fraser was one of sixty-five black female physicians in the U.S.8

When word of her death reached the Dominican Republic, President Trujillo declared a nine day period of mourning with flags flown at half-staff. In 2000, to mark the anniversary of her birth, SUNY Upstate Medical established a scholarship and annual lecture in her name. A portrait of her hangs in the health sciences library and Sarah Loguen Place is the name of the street adjacent the medical school hospital. In 2005, a park was dedicated near her birth home and the Dr. Sarah Loguen Center was opened in 2008 by the Upstate Medical University.9

Image Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sarah_Loguen_Fraser

1 Women in Medicine and Science at Upstate: Sarah Loguen Fraser https://guides.upstate.edu/women-in-medicine/fraser (Accessed November 11, 2019)

2 American National Biography https://doi.org/10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.1302676 (Accessed November 11, 2019)

3 Ibid

4 Journal of the National Medical Association. Sarah Loguen Fraser, MD (1850-1933): The Fourth African-American Woman Physician, Eric v. d. Luft 92:3:149-153:March 2000

5Ibid

6 Wikipedia Sarah Loguen Fraser https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sarah_Loguen_Fraser (Accessed February 21, 2020)

7https://doi.org/10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.1302676 (Accessed November 11. 210190

8Ancestry https://iloveancestry.net/post/63770449503/blackedu-dr-sarah-loguen-fraser-an- amazing (Accessed November 11, 2019)

9 https://guides.upstate.edu/women-in-medicine/fraser (Accessed November 11, 2019)

Isabella Maude Garnett (August 22, 1872 – August 23, 1948)

Physician

Isabella was one of seven children born to Daniel F. Garnett and Hannah B. McDuffin Garnet in Evanston, Illinois. Her family was one of earliet African American settlers in Evanston in the community known as Ridgeland Village. Isabella did not attend high school but took classes in Minneapolis and then worked and studied at Provident Hospital in Chicago. She was awarded her medical degree in 1901 from Chicago’s College of Physicians and Surgeons becoming one of first African American women physicians in Illinois.

Initially, she worked on Chicago’s South Side but returned to Evanston in 1905 and married medical student Arthur Butler in 1907. During her return to Evanston, she practiced independently until 1909. Because of increasing segregation in 1910, all hospitals were closed to Blacks for non-emergency care. To meet the needs of the Black community, in 1914, she and her husband Dr. Arthur Butler, opened the Evanston Sanitarium and Training School on the upper floor of their 1918 Asbury Avenue residence in Evanston, Illinois, treating patients with acute diseases.1 The Sanitarium was the first medical center north of the Chicago Loop. With the sudden death of her husband in 1924, Dr. Garnett continued to run the Sanitarium renaming it Butler Memorial Hospital.2

The Great Migration, 1910-1925, saw more segregation and a doubling of Evanston’s Black community. Butler Memorial was the only source of medical treatment to more than 5,000 African Americans.

In 1930, the hospital merged with The Booker T. Washington Association of Evanston and relocated to 2026 Brown Avenue, taking the name The Community Hospital of Evanston.3

Dr. Garnett retired from the hospital in 1945 and had hoped to continue her private practice but she completely retired in 1946. One day after her 76th birthday she died of complications of heart disease in the hospital she founded. Earlier in that year, a day of National Negro Health Week had been dedicated in her honor.4

Image: Evanston Women's History Project. https://evanstonwomen.org/woman/isabella-maude-garnett/

1 Along the Color Line. The Crisis. October 1914. p. 267.

2 Isabella Garnett https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isabella_Garnett#CITEREFPeterson2008 (Accessed January 19, 2021)

3 Ibid

4 https://wiki2.org/en/Isabella_Garnett (Accessed July 13, 2021)

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Artishia Garcia Gilbert (1868-1904)

Physician, Teacher, Women’s Right Advocate

Artishia Gilbert was born in Manchester, Clay County, Kentucky on June 2, 1868. Her family were farmers and moved quite frequently but Artisha made acquaintance with local teachers and soon learned to spell and read.1 During this time, this little girl learned all that she could from contact with the teachers wherever she went, and became so cautious that at four years of age she was often sent alone with a pocket-book two miles to purchase necessaries at store.2 1878, the family moved to Louisville, Kentucky where Artishia was able to enroll in school. She continued her education, becoming a Christian in 1881, and entering the Normal and Theological Institute (later named State University), graduating in 1885 and then enrolled in university studies. During this time, she taught Sunday school and took jobs to assist her mother with her tuition costs. She completed her A.B. degree in 1889, as class valedictorian.3 Prior to enrolling in medical school, Artishia worked as editor of the magazine Women and Children and as a teacher of English and Greek grammar at her alma mater. In 1893, she graduated from the Louisville National Medical College, passed the medical boards and became the first African-American woman to be licensed in Kentucky.4 Artishia has a desire to learn more, so she enrolled in Howard University Medical School and received her Doctor of Medicine in 1897.

Dr. Gilbert married Bernard Orange "B. O." Wilkerson in New York City but returned to Louisville, opened her practice, worked as assistant professor in obstetrics in State University, a superintendent of Red Cross Sanitarium of Louisville and served on the board of Orphans Home in Louisville.

On April 2, 1904, Dr. Gilbert passed away two weeks after the birth of her third child.

Image Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Artishia_Gilbert

1 Everything Explained. Today https://everything.explained.today/Artishia_Gilbert/ (Accessed November 5, 2019)

2 Women of Distinction: Remarkable in Works and Invincible in Character Lawson Andrew Scruggs Raleigh, NC: Privately Published, 1893 pg. 274-276

https://search.alexanderstreet.com/view/work/bibliographic_entity%7Cbibliographic_details%7C3394715?dorpID=3394715#page/337/mode/1/chapter/bibliographic_entity%7Cdocument%7C3394787 Accessed November 5, 2019)

3 The Sacred Tzolk'in of the Maya https://thesacredtzolkin.blogspot.com/2018/06/ (Accessed November 25, 2019)

4 Shawnee Christian Healthcare Center https://www.facebook.com/ShawneeChristianHealthcareCenter/posts/artishia-garcia-gilbert-was-the-first-african-american-woman-to-pass-the-medical/1483167435041364/ (Accessed November 5, 2019)

Eliza Anna Grier (1864-1902)

Physician, Teacher

Dr. Eliza Anna Grier was born a slave in Mecklenberg County, North Carolina and was emancipated as an infant.

Due to financial difficulties, it took Eliza seven years of work and study to graduate from Fisk University. In 1890, she wrote to the Woman’s Medical College asking about the cost and if there was work that she could perform without it interrupting her studies. Since there was nothing, Eliza attended medical school every other year and picked cotton to finance her education. It took another seven years for her graduate in 1897. 1

In 1898, the North American Medical Review who had described her as “coal Black negress” became the first African American female physician licensed in the state of Georgia.2 Dr. Grier was not prosperous because her clients were very poor and she worked in neglected districts. In 1899, she moved from Atlanta to Greenville, South Carolina where she specialized in obstetrics and gynecology. In 1901, she contracted influenza and could not see patients for six weeks. Having never fully recovered, she died in 1902.

Today, there is a scholarship in her name at Ross University School of Medicine available to African-American, Native American, and Hispanic American students.

Image: Changing the Face of Medicine. https://cfmedicine.nlm.nih.gov/physicians/biography_132.html

1 Black Women and the Re-construction of American History. Darlene Clark Hine, Indiana University Press, 1997, page 153.

2 Oxford African American Studies Center. Physicians by Vanessa Northington Gamble. Source: Black Women in America: An Historical Encyclopedia, Second Edition, Oxford University Press, 2005.

http://www.oxfordaasc.com/article/opr/t0003/e0337?hi=2&highlight=1&from=quick&pos=1#match (Accessed November 11, 2019)

Julia R. Hall (1865-1918)

Physician

Julia Hall was born in Dandridge, Tennessee on October 1, 1865. She graduated from Howard University Medical School in 1894. Dr. Hall was the first female gynecologist on staff at the Freedmen’s Hospital from 1894-1896, she was also the matron and university physician at Howard University. Dr. Hall was the first woman to receive that appointment.1

Dr. Hall opened her practice at 1517 M Street in Washington, DC where she saw patients from 8am to 10am and from 2pm to 4pm in 1901, according to the Union League Directory. In 1894, she, the first woman, was appointed to the Board of Children’s Guardians, until 1913.2 At first it was a salaried position but in 1906 she was paid based on services up to $100 a month.

It is unknown when or if she retired but at the time of her death on April 28, 1918, she lived at 913 S Street NW in Washington, DC.

1 Black Women in America: An Historical Encyclopedia. Editors Darlene Clark Hine, Elsa Barkley Brown, Rasalyn Terborg-Penn. Indiana University Press, 1993, page 517.

2 Ibid

Halle Tanner Dillon Johnson (1864-1901)

Physician, Teacher

Halle Tanner was one of seven children born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania to Benjamin Tucker Tanner and his wife Sarah, an escaped slave.1 Benjamin Tanner was a bishop in the African Methodist Episcopal Church and the home often hosted political and cultural discussions involving other prominent leaders of the time. She married Charles Dillon in 1886 who died suddenly and she returned home as a single mother. It was then that she decided to enroll in the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania, graduating in 1891 with honors.2

Just before graduation, Booker T. Washington wrote to the college seeking a recommendation for a resident physician for Tuskegee Institute, Halle applied for the position. In order to take the position, she had to pass the rigorous ten day licensing examination, this caused tremendous uproar in Montgomery. At the time, she had a choice of taking the boards before any county board or at the state board in Montgomery. She chose to take it at the state in Montgomery. Her examiners were some of the prominent physicians in Alabama and she so impressed the members of the board that her performance on the examination was noted in the 1892 journal of the Medical Association of the State of Alabama Transactions.3 Upon passing the examination, she became the first licensed female physician in Alabama.4 Because of her success which was widely noted, it called attention to the double standard regarding race. Anna M. Longshore, a white woman, failed the exam earlier but practiced medicine in Alabama without a license.5

During her time at Tuskegee, Dr. Tanner established a training school for nurses and founded the Lafayette Dispensary. She also taught two classes a day.6

In 1894, she married Reverend John Quincy Johnson, an AME minster and math instructor at Tuskegee. The couple moved to Columbia, South Carolina where Reverend Johnson had been named president of Allen University. They later moved to Hartford, Connecticut, Atlanta, Georgia, and Princeton, New Jersey as Reverend Allen pursued degrees in theology. In 1900, they settled in Nashville, Tennessee with their three children.

Dr. Johnson died on April 26, 1901 from childbirth complications.

Dr. Johnson was the younger sister or the artist Henry O. Tanner.7

Image Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Halle_Tanner_Dillon_Johnson

1 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Ossawa_Tanner (Accessed November 5, 2019)

2Changing the Face of Medicne https://cfmedicine.nlm.nih.gov/physicians/biography_172.html (Accessed November 5, 2019)

3 Encyclopdia of Alabama http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-3925 (Accessed July 23, 2020)

4 Up/Closed https://upclosed.com/people/halle-tanner-dillon-johnson/ (Accessed November 5, 2019)

5Black Women in America. Indiana University Press, 1993 by Carlene Clark Hine, Elsa Barkley Brown, Rosalyn Terborg-Penn, page 643

6 FamPeople.com https://fampeople.com/cat-halle-tanner-dillon-johnson (Accessed November 5, 2019)

7The Federalist https://thefederalist.com/2019/02/26/meet-black-american-women-smashed-stereotypes-achievement/ (Accessed November 5, 2019)

Sarah Garland Boyd Jones (1866-1905)

Teacher, Physician

Sarah Boyd was born in Albemale County, Virginia to Ellen D. Boyd and George W. Boyd, a builder. Her father constructed the True Reformer building which was placed on the National Historic Register in 19891. After graduating from the Richmond Colored Normal School, she taught school in Richmond, where the family had relocated a number of years before. Sarah married Miles Berkley Jones, a teacher, in 1888 and could no longer teach as a married woman. In 1890, she enrolled in Howard University Medical School, graduating in 1893 upon which she passed the Virginia Medical Examining Board’s examination and became the first woman of any race to be licensed in Virginia.2 Sarah received the highest scores in surgery, practice and hygiene of the eighty-six applicants.3

Dr. Jones and her husband, who also became a doctor, had thriving practices. She treated women and he treated men. Dr. Jones because of fair skin was thought not to be black. In 1898, her and her husband, founded a patient-care facility called the Women’s Central Hospital and Richmond Hospital which cared primarily to women.4 In 1902, she, her husband and other doctors started the Medical and Chirurgical Society of Richmond, since medical societies were not open to them. Seeing a need for a hospital open to blacks, Richmond Hospital was founded and a nursing school was also established. The name changed after incorporation, in 1912, to the Richmond Hospital Association and Medical College, and Training School for Nurses, Incorporated. Richmond Medical Society, which was renamed in 1922 as Sarah G. Jones Memorial Hospital, Medical College and Training School for Nurses was named in her honor in 1922.5

Dr. Jones died at her home on May 11, 1905. At the time of her death, she was the only African-American woman practicing medicine in the Commonwealth.6

Image: Changemakers. https://edu.lva.virginia.gov/changemakers/items/show/97

1 Encyclopedia Virginia https://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/Grand_Fountain_of_the_United_Order_of_True_Reformers

2 Woman’s Legacy: Essays on Race, Sex, and Class in American History. Bettina Aptheker University of Massachusetts Press, 1982, p. 99

3https://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/Grand_Fountain_of_the_United_Order_of_True_Reformers

4 Black Women in America: An Historical Encyclopedia. Editors Darlene Clark Hine, Elsa Barkley Brown, Rasalyn Terborg-Penn. Indiana University Press, 1993, p. 654

5 https://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/Grand_Fountain_of_the_United_Order_of_True_Reformers

6 Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/38448937/sarah-garland-jones

Sophia Bethena Jones (1857-1932)

Physician, Educator

Sophia Bethena Jones was born in Chatham, Ontario to James Monroe Jones and Emily F. Francis Jones in 1857. Her father was a gunsmith, a magistrate, a colleague of John Brown and one of the first black graduates of Oberlin College.

Sophia was frustrated by the limited medical education for women at the University of Toronto. So she enrolled in the medical school at the University of Michigan where she graduated in 1885 and became the institution's first African American female doctor.1 In 1885, she became the first Black faculty member at Spelman College and while there, she organized the school’s nursing program. In 1890, Dr. Jones was awarded a patent for the barrel trunk.3 Upon leaving Spelman, she worked at Wilberforce University and also practiced medicine in St. Louis, Philadelphia, and Kansas City.

Dr. Jones was passionate on the subject of advancing public health and addressing health disparities. In 1913, she published a retrospective article titled, “Fifty Years of Negro Public Health.” Her words ring as prophetically true today as they did when she first penned them: "It is not too much to expect victory for a race, which, in fifty years, has reduced its illiteracy from an estimated percentage of 95 to one of 33.3 as given by the census figures of 1910. Let the teaching of general elementary physiology, including sex physiology, and sanitation be placed on a rational basis in all colored schools and colleges, in the hands of men and women thoroughly trained and with full knowledge of the health problems named above, and there can be little doubt that the issue of the conflict will be such a rapidly declining death rate and reduced morbidity as will astonish the civilized world."4

Dr. Jones and her sister, Anna, an educator, retired to Monrovia, California where they ran an orange grove until their deaths in 1932.

The University of Michigan Medical School offers a lectureship in infectious diseases named for Sophia B. Jones. There is also a Fitzbutler Jones Alumni Society, established by black alumni in 1997, and honoring her and the school's first black graduate, William Henry Fitzbutler.5 A conference room at the University named for Dr. Jones.

Image Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sophia_B._Jones

1 Women at Michigan; The Dangerous Experiment, 1870s the present. Ruth Bordin, University of Michigan Press, 1999, p. 38. http://books.google.com (Accessed November 12, 2019)

2 Spelman College Our Stories Sophia B. Jones Charts a Course of Success for African-American Doctors April 2016 https://www.spelman.edu/about-us/news-and-events/our-stories/stories/2016/04/01/sophia-b.-jones (Accessed November 12, 2019)

3 Canadian Patent Office Record, Volumes 17-18 Index to Volume 18 p. iv

4 Building the Next Generation of African-American Physicians Medicine at Michigan https://www.spelman.edu/about-us/news-and-events/our-stories/stories/2016/04/01/sophia-b.-jones (Accessed November 12, 2019)

5 Building the Next Generation of African-American Physicians Medicine at Michigan (Fall 2002): 34-35. http://www.medicineatmichigan.org/sites/default/files/archives/fitzjones.pdf (Accessed November 26, 2019)

Verina Harris Morton-Jones (1865–1943)

Physician, Suffragist, Clubwoman

Verina Harris was born in Cleveland, Ohio. Little is known after her birth but the family moved to Columbia, South Carolina where her father an AME minister has been assigned. She graduated from the University of North Carolina in 1877, the only year when Negroes graduated.1 She entered Women’s Medical College of Pennsylvania in 1884, graduating in 1888. Following graduation, she moved to Holly Springs, Mississippi, become the resident physician at Rust College and the first woman to pass Mississippi’s medical board examination and first woman to practice in the state.2 In 1890, she married Dr. Walter A. Morton, moved to Brooklyn, New York where they set up their practice and became the first Black woman physician practicing in Nassau County.3 Dr. Walter Morton died in 1895 but Verina continued the practice, active in the Kings County Medical Society and the National Association of Colored Women directing their Mother’s Club.4 Dr. Morton-Jones was very active in the community as member or leader of the Committee for the Improvement Condition of Colored Women and the National Association of Colored Women, both precursors of the NAACP. Condition of Colored Women and the National Association of Colored Women, both precursors of the NAACP. She was also a founding member of the Urban League in Brooklyn and owner of the building that housed it, the founder and head worker of the Lincoln Settlement House in Brooklyn, the president of the Brooklyn Equal Suffrage League, a speaker at the Phillis Wheatley branches of the YWCA on hygiene and health, a director of the Brooklyn Mothers' Club, a member of the interracial Cosmopolitan Club (a social and political group of New York City and Brooklyn reformers), and most frequently cited as “the first and only African American woman to serve on the Executive Board of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People,” which she did from 1913 to 1923.5

Dr. Morton-Jones suffered many disappointments in her life. Beginning in 1895 when her husband and daughter died. In 1901, her mother died and her sister died in 1906. Her nephew, McCants Steward, a prominent attorney, with whom she regularly corresponded committed suicide in 1919 and his brother Gilchrist died in 1926. Once again, Dr. Morton-Jones was left a widow by Emory Jones, whom she married in 1901 and he died in 1927.

After having lost the two people closest to her, she moved to Hempstead, Long Island and resumed her medical practice, campaigned for her son-in-law, organized the Harriet Tubman Community Club.

Dr. Morton-Jones died on February 3, 1943.

1 The Crisis. March 1943 pg. 86 Woman Physician Dies Vol. 50, no. 3

2 https://everipedia.org/wiki/lang_en/Verina_Morton_Jones/

3 Ibid

4 Ibid

4 http://www.oxfordaasc.com/article/opr/t0001/e3414

Francis M. “Fannie” Kneeland (1873?-)

Physician

Born in Tennessee and orphaned. She raised her younger siblings educating them and herself.

Francis graduated from Meharry with honors in 1898. By 1907-08 her name appears in the Memphis directory as physician and surgeon. In addition to her practice, which was on Beale Street serving a diverse and multiethnic community, Dr. Kneeland was associated with University of West Tennessee in Memphis and in 1923 served at the head instructor of the nursing program.1 She was active in organizations that worked to for uplift and improvement of black women. She was only black woman physician specializing in obstetrics and gynecology in the city and therefore, the preferred physician.2 Her practice afforded her the ability to purchase a home in one of more prosperous section of the city.

Dr. Kneeland was so highly thought of that, Juvenile Court Judge Camille Kelly would often send delinquent and indigent black girls to her to help them find their way in life and become respectable citizens.3

She later moved to Chicago, it is unknown when or why.

Image Our Memphis History https://ourmemphishistory.com/dr-francis-kneeland-forgotten-hero/

1 Our Memphis History A Memphis Conversation (2018) http://ourmemphishistory.com/dr-francis-kneeland-forgotten-hero/ (Accessed November 15, 2019)

2 Facts on File encyclopedia of Black women in America Science, Health, and Medicine pg 94

By Darlene Hine Copyright 1997 published by Facts on File, Inc. New York

3 Our Memphis History A Memphis Conversation (2018) http://ourmemphishistory.com/dr-francis-kneeland-forgotten-hero/ (Accessed November 15, 2019)

Eunice P. Shadd Lindsay (1848-1887)

Physician

Eunice Shadd was born in Chatham-Kent, Ontario, as one of 13 children born to free African Americans Abraham D. Shadd and Harriet Buron Parnell. She left Canada moving to Washington, DC to be with two of her siblings and in 1872, Dr. Lindsay graduated from Howard University Normal School. She taught public school for several years before enrolling and graduating as one of the first black female from Howard University Medical School in 1877.1

After graduating in 1877, she married Dr. Frank T. Lindsay and moved to Xenia, Ohio where both practiced medicine.

Dr. Eunice Shadd Lindsay died on January 4, 1887 in Xenia, Ohio.2

1 Oxford African American Studies Center Physicians Vanessa Northington Gamble Black Women in America

2 Beckford, Geraldine Rhoades (2013). Biographical Dictionary of American Physicians of African Ancestry, 1800-1920. Africana Homestead Legacy Pb. pp. 199, 288. ISBN 9781937622183 (Accessed November 11, 2019)

Alice Woodby McKane (1865-1948)

Physician, Politician, Author, Suffragist

Alice Woodby was born in Bridgewater, Pennsylvania to Charles and Elizabeth Fraser Woodby. By time she turned seven, she had lost both parents and as a result suffered traumatic blindness for three years.1 She attended Hampton Institute and the Institute for Colored Youth (Cheyney State University) and in 1889, she enrolled in the Woman’s College of Pennsylvania graduating in 1892 with high honors winning three competitive prizes in science, English, and literature.2

In 1893, she and her husband, Cornelius, who was also a physician, moved to Savannah making her the only African American female physician in the state.3 Alice and Cornelius founded a training school for nurses becoming the first nursing school in Southeast Georgia. The school was a two year program for females and males where they studies anatomy, physiology, hygiene, midwifery, therapeutics, chemistry, medical nursing, surgical nursing care of women in confinement and cooking for the sick.4. The couple moved to Monrovia, Liberia, because of her husband’s desire to give something to his ancestral home, and established the first hospital in Monrovia along with a drugstore and nurse training school. Their stay was cut short because Alice contracted African fever so the couple moved back to Georgia. After regaining her health, she established the McKane Hospital for Women and Children. The hospital later renamed the Charity Hospital was a forerunner of the community not-for-profit hospital.

To provide a better education for her children, the family moved to Boston in 1909, two years after their arrival, she took and passed the Massachusetts State Medical Boards..5 After the passing of her husband in 1912, Alice continued the practice, limiting it to the care of female diseases, and became more involved in politics. She joined the NAACP, was a Republican committee chairwoman, and participated in the suffragist movement. In 1913, her first book The Fraternal Sick Book was published and Clover Leaves, a book of poetry, was published in 1914.6

Dr. McKane died of arteriosclerosis on March 6, 1948.

Image Georgia Women of Achievement https://www.georgiawomen.org/alice-woodby-mckane

1 Elmore, Charles J. Black Medical Pioneers in Savannah, 1892-1909: Cornelius McKane and Alice Woodby McKane. Georgia Historical Quarterly Vol. 88, No. 2 (summer 2004), 179-196 https://www.jstor.org/stable/40584737 (Accessed November 11, 2019)

2 Ibid

3 Georgia Women of Achievement https://www.georgiawomen.org/alice-woodby-mckane (Accessed November 11, 2019)

4 The Doctors McKane Evelyn W. Parker http://libweb.lib.georgiasouthern.edu/armstrong/SavBio/McKane_Cornelius%20and%20Alice.pdf (Accessed November 11, 2019)

5 Ibid

Mary Susan Moore (1865-1965)

Physician

Mary Susan Moore was born in Chatham County, North Carolina. Dr. Moore received her medical degree from Meharry Medical Department of Central Tennessee College in 1898. She moved to Texas and becoming the first African American female physician in the state. In 1903, she and husband, Dr. James D. Moore opened a forty-bed hospital to serve the Black community in the city of Galveston. There was much opposition to this by residents and the local government, ordinances were enacted to stop this endeavor. By 1907, the city of Galveston, repealed the ordinance and the Hubbard Sanitarium was opened. Dr. Moore and her husband maintained the hospital until 1925.

Dr. Moore died on August 22 1965.

Mary Susan Moore Medical Society https://marysusanmooremedicalsociety.org/ (Accessed January 19, 2021)

Lucy Ella Moten (1851-1933)

Educator and Physician

Lucy Moten was born in Fauquier County, Virginia to free parents, Benjamin and Julia, nee Withers, Moten. Her parents recognized her promise, so the family moved to Washington, D.C., for provide her better educational opportunities. She attended Howard University training as a teacher, and in 1870, she began teaching primary school. Graduating in 1875 from the State Normal School in Salem, Massachusetts, she returned to Washington, DC. Back in Washington, she pursued her dream of becoming the principal of the Miner Normal School. Frederick Douglass recommended her for the position but she initially turned down because despite her educational qualifications, the board said that her striking appearance and her character, were deemed not moral or strong enough to assume the position. After promising to give up her recreational activities such the theater, card playing and dancing, she appointed principal.1

It was noted that during an examination of the school, that it was hard distinguish between the teachers and students due to the training that the students were receiving.2 With a desire to give her students, not only a quality education but she also wanted to educate them in hygiene, health and physiology. Lucy enrolled in Howard University Medical School, graduated in 1897, and established a health and hygiene program not only for the students but also as part of their teaching curriculum including lectures on childhood diseases.

As an educator, Dr. Moten travelled extensively in the United States and Europe, and graduates of the Miner Normal School, widely sought in the United States.

Dr. Moten never established a practice outside the School and retired in 1920, moving to New York City.

She struck by a car in Times Square and died on August 24, 1933. In her will, she left the sum $51,000, to Howard University and a school, was named in her honor.

Image Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lucy_Ella_Moten

1Notable American Women, 1607-1950: A Biographical Dictionary Volume 2 Gale Research Inc, Staff Editor Jessie Carney Smith 1992. ISBN 0674627342, pg. 591.

2 ”[The National Capital. A Bourbon Senator's Diatribe in Opposition to the Education Bill--Passage of” New York Globe April 12, 1884

Emma Wakefield-Paillet (1869-1946)

Physician

Emma Wakefield-Paillet was born on November 21, 1869 in New Iberia, Louisiana to Samuel and Amelia Valentine Wakefield. Her father, Samuel, served the New Iberia Parish as postmaster, tax collector, colored school district director and state senator. He and his wife desired a good education for their seven children so that they could take leadership roles in post-Civil War Louisiana. The family was banished from New Iberia after her brother was lynched stemming from an incident with a white merchant.1 Emma and her siblings attended New Orleans’ Straight University. After graduation, she attended and graduated with honors from the medical program at New Orleans University, as one of three students and the only female in 1897. Upon completion of her examination for licensure, it was recorded in the minutes of the Louisiana State Board of Medical Examiners: “The colored woman passed an exceptionally good examination and the Board made special mention of her case.” She set up her practice at 1233 N. Villere Street in New Orleans.2

In 1900, Dr. Wakefield with her husband Joseph Oscar Paillet along with several family members moved to San Francisco. Because of their complexion, they were often listed as white, but it is not known if they used the error to pass for white.2 In 1901, she was granted a license to practice medicine in California. Except for periodic trips to Louisiana, she lived most of her life in California, where she died in 1946.

A play about her life, The Forgotten Healer by Ed Verdin was performed in 2018 and a historical marker was erected describing her significance.3,4

1 The Forgotten Healer. https://pwcenter.org/play-profile/forgotten-healer(Accessed January 28, 2021)

2 64 Parishes. https://64parishes.org/emma-wakefield-paillet-md (Accessed January 28, 2021)

3 The Forgotten Healer. https://pwcenter.org/play-profile/forgotten-healer (Accessed January 28, 2021)

4 Louisiana's First Black Female Physician Dr. Emma Wakefield~Paillet. https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=129769 (Accessed January 28, 2021)

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Beulah Wright Porter Price (1869-1928)

Physician, Teacher, Community Activist

Beulah Wright, born January 2, 1869, was not only a physician, she was also an educator and active participant in the African American women’s club movement in Indianapolis, Indiana. Upon the establishment of her medical practice in 1897, she became the first African American woman physician in the city to open a practice.1 She remained in private practice until 1901 and in 1905 became a principal of a public school in Indianapolis.2 Dr. Porter combined her medical expertise and her love of community activism to cofound the Women’s Improvement Club (WIC) of Indianapolis, with Lillian Thomas Fox.3 The organization started as a literary but quickly pivoted to a charitable organization whose goal was to fight tuberculosis. In 1905, Fox, Porter, Ida Webb Bryant and members of the WIC established a tuberculosis camp to treat infected African American children.4 Although Dr. Porter had given up her medical practice, she remained active in other local clubs, she served as an officer of the Grand Body of the Sisters of Charity, the Parlour Reading Club, the Mayflowers Club, and the local chapter of the NAACP.5

Dr. Porter’s first marriage to Jefferson D. Porter was on March 8, 1893.

She married Walter M. Price on November 14, 1914.6

1Moment of Indiana History. "Above And Beyond: Lillian Thomas Fox & Beulah Wright Porter". https://indianapublicmedia.org/momentofindianahistory/lillian-thomas-fox-beulah-wright-porter/. Retrieved 2022-12-13

2The Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. Beulah Wright Porter Price - indyencyclopedia.org. Retrieved 2022-

3Moment of Indiana History

4 The Encyclopedia of Indianapolis Beulah Wright Porter Price - indyencyclopedia.org

5 Ibid

6 Ibid

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Sarah Parker Remond (1826-1894)

Physician, Abolitionist

Sarah Parker Remond was born in Salem, Massachusetts on June 6, 1826 to John and Nancy Remond. She received limited education in primary school and was basically self-educated reading books, magazines, pamphlets and borrowed materials from friends.

She came from a family of abolitionists and was taught about the horrors of slavery through her family’s work and her home being a stop on the underground railroad. Also, her brother, Charles Lenox Remond, was an antislavery lecturer in the United States and Britain. Sarah started to travel with him on his speaking tours. In 1853, after purchasing a ticket she was denied a seat at the performance of the opera Don Pasquale at Boston’s Howard Athenaeum. She was forcibly ejected and pushed down a flight of stairs and suffered an injury. She sued the managers and won $500 which she did not care about but the vindication.1

In 1859-1860, Sarah gave 45 lectures in 18 cities and towns in England, three cities in Scotland, and four cities in Ireland using the story of Margaret Garner.2 Margaret Garner was an enslaved women who murdered her child after she recaptured under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Early in 1859, she desired to go to France and went to the American Embassy to obtain the necessary visa and Mr. Dallam, an official, refused upon the grounds that colored people are not citizens of the United States. She later received a passport through the British foreign secretary3 during this time, she was a founding member of Ladies’ London Emancipation Society4 and active in the Freedmen’s Aid Association of London.5

With the outbreak of the War Between the States, Sarah urged Britain to purchase cotton from India and for the British people to boycott cotton from the United States. She pointed out the fact that in England, factory workers and mill hands are paid for their labor but that the people picking the cotton were not. Despite the situation of low wages and unsafe conditions, among these workers, the boycott held.

Sarah had been a lifelong learner and she enrolled in Bedford College for Women University of London studying history, elocution, music, English literature, French and Latin.6

After the Civil War, in 1866, Sarah made the decision not to return to the United States to face the discrimination she knew existed. After visiting Rome and Florence, she settled in Florence and at the age of forty-two entered the Santa Maria Nuova Hospital. Sarah graduated in 1871 and practiced medicine in Florence. Her practice flourished and she married a Sardinian painter named Lazzaro Pinto Cabras.

Dr. Remond died in Florence in 1894 and is buried in Rome in the Non-Catholic Cemetery. In 2014, a memorial plaque was put up in her memory.7

Image Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sarah_Parker_Remond

1Black Women in America: An Historical Encyclopedia. Editors: Darlene Clark Hines, Elsa Barkley, Rosalyn Terborg-Penn, Indiana University Press, 1993, p. 972

2 Josie Holford: Rattlebag and Rhubarb – Sarah parker Remond and the Cotton Workers of Lancashire https://www.josieholford.com/remond/ (Accessed November 28, 2019)

3 The Journal of Negro History Vol. 20, No. 3, Jul., 1935 pg. 291 Sarah Parker Remond, Abolitionist and Physician https://www.jstor.org/stable/2714720 (Accessed November 28, 2019)

4 University of London A voice for freedom: The life of Sarah Parker Remond https://london.ac.uk/news-and-opinion/leading-women/a-voice-freedom-life-sarah-parker-remond (Accessed November 28, 2019)

5 The Journal of Negro History Vol. 20, No. 3, Jul., 1935 pg. 291 Sarah Parker Remond, Abolitionist and Physician https://www.jstor.org/stable/2714720 (Accessed November 12, 2019)

6 Josie Holford: Rattlebag and Rhubarb – Sarah Parker Remond and the Cotton Workers of Lancashire https://www.josieholford.com/remond/ (Accessed November 12, 2019)

7 University of London A voice for freedom: The life of Sarah Parker Remond https://london.ac.uk/news-and-opinion/leading-women/a-voice-freedom-life-sarah-parker-remond (Accessed November 12, 2019)

Emma Ann Reynolds (1862-1917)

Nurse, Doctor

Emma Ann Reynolds was born in 1862 in Frankfort in Ross County, Ohio.

Upon graduating from Wilberforce University, Emma moved to Chicago hoping to become a nurse but she had been turned down because of her color. Her brother was a friend of Dr. Daniel Hale Williams and he brought her case before him. At the time there were no hospitals in Chicago that admitted black patients, allowed black physicians to practice, admitted black physicians to residency programs, basically all African Americans in Chicago were denied health care or continuance of their education. Dr. Williams and others including Emma Reynolds, in 1891, opened the interracial medical facility Provident Hospital and Training School.1 Emma graduated from there in 1893 and entered the Medical College of Chicago at Northwestern University, becoming the first African American woman admitted. After her graduation in 1895, she was the supervisor at the Training School for Nurses before becoming the resident physician of the Paul Quinn College in 1896 but later that year she moved to Waco, Texas. In 1899, Dr. Reynolds was an active member of the Frances Willard Woman’s Christian Temperance Union in New Orleans, Louisiana as the Superintendent of Purity Work.2 She practiced there until 1902, when she moved back Frankfort, Ohio and practiced medicine until her death in 1917.

In 1990, the Provident Hospital Nurse Alumni Association erected a tombstone for Dr. Emma Reynolds in Greenlawn Cemetery, Frankfort, Ohio.3 Dr. Reynolds was inducted into the Chillicothe-Ross County Women’s Hall of Fame in 1991 in recognition of her medical contributions and in 1994, she was inducted into the Ohio Women’s Hall of Fame. In 2001, Dr. Reynolds was recognized for her pioneering role during Women's Month, by the U.S House of Representatives.4

Image Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emma_Ann_Reynolds

1 Provident Hospital A Hospital of Hope http://74852222.weebly.com/emma-reynolds.html (Accessed November 11, 2019)

2The Temperance Cause Times-Picayune (New Orleans, Louisiana) May 12, 1899, p. 3.

3The Provident Foundation http://provfound.org/index.php/history/history-emma-reynolds (Accessed November 11, 2019)

4 Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emma_Ann_Reynolds (Accessed November 11, 2019)

Harriet Alleyne Rice (1866-1958)

Physician

Harriet Rice was born in Newport, Rhode Island and spent most of her life in the family home. She graduated from Rogers High School and then from Wellesley College in 1887 as the first African American to do so. Soon after she graduated with a medical degree from University of Michigan Medical School, she went to the New York Infirmary for Women and Children for further training. Because of racism, she not allowed to practice at any American hospital so she joined Jane Adams at Hull House in Chicago providing indigent care.

At the start of World War I, she tried to join the American Red Cross but was denied because of her color so she contacted the French embassy and they were more than willing to accept an experienced doctor. Dr. Rice served from January 1915 to a few days after the armistice. In 1919, she was recognized for her war effort not by the Americans but the French and was awarded the National Medal of French Gratitude.

Dr. Rice returned to America and practiced medicine for another 40 years. She died in 1958 in Worcester, Massachusetts.